Kosovo during the Middle Ages

One of the most important elements of Balkan history has been the important role myths have played in history of some of the countries. It is a reality, the creation of Serbian and Greek (modern) ethnicities owe their creation to myths. These myths proved expedient during their national revival and afterwards, during which time they took precedence over national culture and state strategies. This is best exemplified by their anti-Albanian policies which were built on baseless myths. The intrusions into Albanian territories were given a totally different face and glorified. The autochthonous population did not fit at all in this scheme of things, of importance was only Serbian greatness in Kosovo and for the Greeks their idea of Greek Epirus.

As days of Ottoman Empire were coming to an end, the extremist elements devised plans to correct historic injustices that were bestowed on them and establish control over land they designated as belonging to them. Hence comes the myth that the Albanians had intruded to the land that belonged to them. To correct this historic injustice, extremist policies were devised against the majority autochthonous population of these territories. This population was subjected to a position of a people who had intruded on Serb and respectively Greek domains, and as such, even extermination policies would be acceptable.

+ Continue reading

In this essay I will focus on the main Serbian claim that Kosova was Serb and was populated by Serbs until the Albanians flooded in after 1690. This idea was put forth by a number of historians with J. Cvijic as their main representative. This myth took hold and inspired Serbian historians and politicians to this day. This is not the only anti-Albanian Serbian myth; on the same level is their claim that Kosovo was their cradle of nationhood, their claim of construction of churches (when in reality it was a takeover of existing churches) and their glorifying claim about the Battle of Kosovo (as if they were the only people that fought the Ottoman invasion), etc.

Unfortunately the Serbian and Greek mythical views dominated in the propaganda war for some time. This was due mainly to the inadequate Albanian effort to enlighten their history and also inadequate interest by foreign historians to challenge these claims. It was the Kosovar historians, M. Ternava, S. Gashi, I. Ajeti, R. Doci, L. Mulaku, R. Islami, and H. Islami who courageously challenged the Serbian view. Then followed the researcher S. Pulaha in Tirana, who researched Turkish archives for information about the ethnic status of the area at the time the Ottoman commenced. A summary of S. Pulaha’s findings follows:

The registers of the census of the land and population of the Sandjaks in the 15th-16th centuries are important sources of information as to the population of the territories at the earliest stage of the Ottoman occupation, such as ethnic composition of the population, the degree of the implantation of timar system, as well as cultural effect the occupation was having on the people. On this occasion I will limit myself on the information these registers provide about the extension of the Albanian population in the territories of today’s Kosova/Kosovo.

Registration of land and population of Shkodra Sandjak in 1485 includes information on an area that extending between Tropoj, Junik and Gjakove, known as Altun-Alia. Areas to the north and south of this district were not included in the Shkodra Sandjak. This district included 53 villages with 926 households, 356 able-bodied men and 99 widow households. The register recorded the names of the heads of the families, the able-bodied and widows of each village that was responsible for dues.

This period is reflective of the period of when Ottomans had just taken over the area and organized it administratively, and Islam had not as yet taken hold. Thus the names of the inhabitants reflect their religious affiliation prior to the conversion to Islam. The tendency being that the Catholics maintained their Albanians names while others had either Slavic names or a mix of Slavic-Albanian names.

Albanian researcher used this criteria in identifying the ethnicity of the inhabitats, and based on this, he stated the plain between Gjakova and Junik in the 15th century was without a slightest doubt a territory inhabited entirely by Albanians. He also adds that on the higher grounds, towards Tropoja, there were villages where the inhabitants exhibited Slavic names and Albanian names are not in preponderance. But at the same time, S. Pulaha observed, there were cases of Albanian families also used Slavic names. Here is how this phenomenon appears: Radosavi, son of Gjon; Vladi, son of Gjon; Bozhidari, son of Gjon; Gjorgj Mazaraku or Vulkashin Zhevali and Gjon, his son; Leka son of Mirosavi; Dejan, son of Gjon; Novak, son of Gjon; Ukca Stepani, son Leka Stepani and grandson of Stepan Leka; Milen son of Daba and his son, Lleshi the son of Milen; Gjon Bogoi and Ivan, his son; Lleshi son of Gjorgji, Tanushi son of Radsave; Bogdan, son of Novak, Dimitri, his brother, and Duka, his brother.

Pulaha indicates that there are many other such cases. There are also Albanian names with Slavonic adaptations, such as Lekac from Leka, Nikac from Nika, Dedac from Deda. More telling in this regard is information about the Vilayet of Kecova, located to the south of Altun-Alia which relates to the period of Bayazid the Second. The ottoman register divides Kercova into Albanian (arvnanvud) and Serb (serf) quarters. Pulaha indicates that the inhabitants of the Albanian section are indicated to bear not Albanian but Slavonic names. This would support the view that at this time Albanians also bore Slavic names, and it would be wrong, as some have done, to consider these inhabitants as being of Serb ethnicity.

S. Pulaha studied the 1582 (about a century later) Shkodra registers for the subject area and here is what he observed. The situation had not changed with villages that had indicated a predominance of Albanian names in 1485. In the villages of Shipcan, Gosturan, Cernomile, Stepaneselo, Trebnosh, where in 1485 Slavonic names predominated, in 1583, Albanian names predominate. In many other villages where Slavonic names were in use by the majority, such as Polja (Poliba), Shuma, Jasiq, Kovac (Kovacica), Goran, the number of inhabitants with Albanian names increased further. In some villages such as Sqavica, Rjenica, Miholan, Nebonani (Tebojani), Slavonic names continued to predominate in the 16th century as they did in 1485.

Pulaha indicates that a minority on inhabitants of areas analyzed above were exhibiting Islamic names in 1583. But the cities, on the other hand, had experienced a drastic increase in the population with Islamic names; and the increase seemed to have continues with more conversions as indicated by column 2.As we can see in Peja, Gjakova, Prizren, Vucitern, and Prishtina, the Moslem names of heads of families were in the majority (1006). By all indications this Muslim population consists of Albanian converts. That these converts were Albanian is seen by the retention of Albanian surnames by many. (See page 412)

The Albanian ethnicity of this community is also ascertained by Papal envoys who visited these territories at the beginning of the 17th century. Pjeter Mazreku wrote (1623-1624) Prizren has 12,000 Turkish souls, nearly all of them Albanian; of this nationality only about 200 souls may be Catholic There are also about 600 Serbian souls. The archbishop of Tivari, Gjergj Bardhi, after a visit to the Dukagjini Plateau in 1638 said of this area, All these above mentioned places (in the Prizren-Gjakove stretch) are Albanian and speak the same language. Turkish geographer , Hadji Kalfa said that Prizren was inhabited entirely by Albanians. The renowned Turkish traveler, Evliyan Celebi, writing about Vucitern (16th Century) which he had visited, said that its inhabitants spoke Albanian, not Slavic, whereas the official language was Turkish.

Of the 547 Christian heads of family about 217 had Albanian or Albanian-Slav names and 330 heads of family had Slav Orthodox or Greek Byzantine religious sphere. By all indications, the former group was made up of individuals with Albanian ethnicity. At least part of the latter group must also be of Albanian ethnicity.

The Serbian anthroponomy certainly was the effect of two hundred years of Serbian political and religious domination of Albanians. Under this reality, many Albanians adapted Serbian names, as they were to adapt Moslem names under Ottoman occupation. But the mass conversion to Islam would indicate that their ethnic dilution was not deep. As the Serbian control ended, Albanians renounced their Serbian names.

The phenomenon of Albanians bearing Serbian names prior to the Ottoman occupation is attested by Mihail Lukarevic, a Dubrovnik merchant who had affiliations in Novoberda during the thirties of the 15th Century. His debtor’s books give a considerable number of people with Albanian names which point to the existence of an Albanian majority in this area. Along with people with purely Albanian names and surnames, there are also mixed Albanian-Slav names or Albanian names with characteristic Serbian suffixes.

In the cadastre books of 1455 in Vucitern and Prishtina areas following type names are found:

Todor, son of Arbanas, Bogdan son of Todor; Radislav, son of Todor; Branislav, son of Arbanas (Kucica village); Bozhidar Balsha (Bresnica village); Radovan, son Gjon (Cikatovo village); Radislav, son of Gjon and Bogdan, his son (Sivojevo villages); Branko, son of Gjon and Radica, his brother; Gjoka, son of Miloslav (Gornja Trepz village), etc.

It is interesting to note that in the 1566-1574 register of Vucitern Sandjak, at location designated as Albanian quarters in Janjeva, nearly half of the inhabitants (84 heads of family and 8 bachelors) carried Slav Orthodox names. Thus, the section identifies as inhabited by Albanians, these inhabitants bore Slavic names or mixed Albanian-Slav names. This phenomenon is observed in many villages of Kosovo and as far north as Kurshumlia and Nish.

The cadaster books indicate that not all Orthodox Christian inhabitants bore names from Slav Orthodox sphere. These names represented a heterogenous mixture of Albanian/Catholic names and names from Greek Byantine sphere, which are in wide use among the Albanians to this day.

The Albanian character of this area is also attested by documents from the Command of the Austrian Army that entered Kosova in 1690 during the Austro-Turkish War. These documents point out that Prizren was considered capital of Albania. The Emperor Leopold I indicated that his armies were fighting in Albania (when they entered Kosova). The same documents indicate that the Austrian forces were met by 5000 Albanian insurgents in Prishtina and 6000 others in Prizren, thus basically confirming the preponderance of the Albanian population in this area.

It is clear that documents disprove the Serbian contention that Albanians had flooded into Kosovo after Serbian mass migration†northward in 1690. Above sources indicate that a century earlier, and most likely ever since the dawn of history, Kosova was inhabited by the same people,that is the Albanians.

Any movement of population from Albanian mountains had to be minimal. In reality, based on these documents, Pulaha indicates, this was not even possible. It is indicated by the last census that between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, the population in the adjoining mountainous areas was very small (see pages 429-430). (***Source data and excerpts taken from Pulaha, S., Shqiptaret dhe Trojet e tyre, 1982, pp.334-452.)

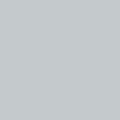

The origin of Kosovo’s Orthodox churches

The ethnogenesis of today’s Serbia begins with the emergence of the Slavic settlements south of Danube River. Historians in general have stayed from the subject as to what followed with Slavic settlements. The simple, idealistic Serbian view is that they came, established empires, and every subject relating to life under these empires relates exclusively to them. As to what happened to the original population of the area, is said nothing, and one is lead to assume that there never was such a population.

The ethnogenesis of today’s Serbia begins with the emergence of the Slavic settlements south of Danube River. Historians in general have stayed from the subject as to what followed with Slavic settlements. The simple, idealistic Serbian view is that they came, established empires, and every subject relating to life under these empires relates exclusively to them. As to what happened to the original population of the area, is said nothing, and one is lead to assume that there never was such a population.

There is no basis to assume that the area was unpopulated or that the original inhabitants had left the area after the Slavs came. At least for the case of Kosovo, knowledge that has come to light after WWII has tended to support the view that the original population had survived the Slavic onslaught and had continued to inhabit the area throughout the middle ages. Here is what well known Yugoslav historians have noted about the survival of the pre-Slavic population of the area. Fannula Papazoglu has indicated that Dardania was one of the Balkan regions less Romanized and that its population seems to have preserved better its individuality and its consciousness from antiquity, and the possibilty that the Dardanians were able to escape Romanization and to have preserved its individuality, cannot be excluded.(Iliri I Albanci, Belgrade, 1988, p. 19) Henrik Baric indicated that the Albanians had inhabited Dardania and Peonia before Slavs settled in these areas.

Click here to continue reading.

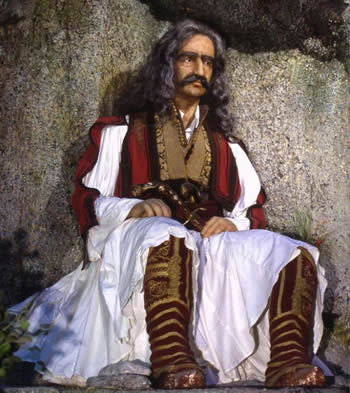

Albanians that made Greece.

According to Kollokotron himself, his grandfather, Jani Bocka consisted of a large stature and had a fairly bonny rear-end. At one time, an Albanian that had been looking at him, remarked: what is this bithgur(lit. stone-posterior)? Since then, indicated Kollokotron, his grandfather was stuck with the nickname "Bithgur", which eventually replaced the family name Bocka. In fact, the meaning of Kollokotron as a word is a direct translation into Greek of Arvanite name "Bithgur", that is hard posterior.

According to Kollokotron himself, his grandfather, Jani Bocka consisted of a large stature and had a fairly bonny rear-end. At one time, an Albanian that had been looking at him, remarked: what is this bithgur(lit. stone-posterior)? Since then, indicated Kollokotron, his grandfather was stuck with the nickname "Bithgur", which eventually replaced the family name Bocka. In fact, the meaning of Kollokotron as a word is a direct translation into Greek of Arvanite name "Bithgur", that is hard posterior.

As it could be imagined, the people called the Elder Bithguri, while today's voluble historians refer to him with the translated name, "Kollokotron", which raises the question: as long as the people devotes its songs to its heroes (in verse and music) in its own language and not in the language of volubels, what has happened to the folk songs about Bithguri? We know songs about Bithguri, but evidently these are songs that have transformed by the volubles and which we today call folk songs, while the original folk songs have been buried by time. And unfortunately, this in not an isolated case.

Click here to continue reading.

Assimilation of Albanians in Greece.

Source: Bintliff, J.L. (2003). The ethnoarchaeology of a 'passive' ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece. In K.S. Brown & Y. Hamilakis (Eds.), The Usable Past. Greek Metahistories, pp. 129-144.

Source: Bintliff, J.L. (2003). The ethnoarchaeology of a 'passive' ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece. In K.S. Brown & Y. Hamilakis (Eds.), The Usable Past. Greek Metahistories, pp. 129-144.

…The Greek national education system (cf. chapter 3 in this volume) stresses the heritage of classical Athens and the continuity of Greek virtues. Indeed, history and archaeology for Greeks today usually all but stop at the Age of Alexander, and the former only picks up again with the War of Independence in the early nineteenth century. During the intervening two millennia of "oppression," the Greek spirit slumbered in chains, with only Byzantine churches and icons to mark the eternal flame. (p. 137)

…Thus from the late nineteenth century onward the children of the inhabitants of the new "nation-state" were taught in Greek, history confined itself to the episodes of pure Greekness, and the tolerant Ottoman attitude to cultural diversity yielded to a deliberate policy of total Hellenization of the populace—effective enough to fool the casual observer. One is rather amazed at the persistence today of such dual-speaking populations in much of the Albanian colonization zone. However, apart from the provinciality of this essentially agricultural province, a high rate of illiteracy until well into this century has also helped to preserve Arvanitika hi the Boeotian villagers (Meijs 1993). (p.138)

…While compiling my maps of village systems across the post-medieval centuries from the Ottoman sources (archives so remarkably discovered and tabulated for us by Machiel Kiel; see Kiel 1997; Bintliff 1995, 1997), I was careful to indicate in the English captions which of them were Albanian speaking and which Greek-speaking villages. A strong supporter of the project, the Orthodox bishop of Livadhia, Hieronymus, watched over my shoulder as the maps took shape. "Very interesting," he said, looking at the symbols for ethnicity, "but what you have written here is quite wrong. You see the people in Greece who speak a language like Albanian are Arvanites, not Alvanoi, and they speak Arvanitika not Alvanika." (p.139)

…Shortlyafter this conversation, I saw the bishop pass across the courtyard of our project base, a converted monastery run as a research center, to talk to the genuine Albanian guest workers who were restoring its stonework. I knew he was himself an Arvanitis, and listened with interest as he chatted fluently to them—and it wasn't in Greek! I was tempted, but wisely forbore, to ask him which language they were conversing in Arvanitika or Alvanika? (p. 139) in.

Ethnicity and religion in Ottoman Empire.

Aided by this privileged position and strong european economic considerations as a trading distribution center, as well as western infatuation with ancient Greece, Greeks were able to create a fast expanding middle class which, in turn, caused an increase in the size of the Greek-speaking population and of groups that identified with the Greek Patriarchate, regardless of their ethnic origins. 47

Click here to continue reading.

Early 19th century Epirus

Ali Pash Tepelena’s rise brought Albania to the forefront of attention throughout Europe and raised the question with many as to how this area fit into the great power game. It was an opportune time for the west European philhellenes to further refocus their attention on the European Turkey and many traveled to the area and included Albania in their itinerary.

Ali Pash Tepelena’s rise brought Albania to the forefront of attention throughout Europe and raised the question with many as to how this area fit into the great power game. It was an opportune time for the west European philhellenes to further refocus their attention on the European Turkey and many traveled to the area and included Albania in their itinerary.

Ali Pash Tepelena’s rise brought Albania to the forefront of attention throughout Europe and raised the question with many as to how this area fit into the great power game. It was an opportune time for the west European philhellenes to further refocus their attention on the European Turkey and many traveled to the area and included Albania in their itinerary.One can easily see that these travelers admired Greece and marveled with ancient Greek history. During that age of revolution many dreamed of finding the ‘Greeks’ ready to claim their history and continue their great past. But the reality on the ground wasn’t a case for optimism. Baron John Cam Hobhouse Broughton gave a reality check about the Greeks:One can easily see that these travelers admired Greece and marveled with ancient Greek history. During that age of revolution many dreamed of finding the ‘Greeks’ ready to claim their history and continue their great past. But the reality on the ground wasn’t a case for optimism. Baron John Cam Hobhouse Broughton gave a reality check about the Greeks:

“A great proportion of those comprehended under the term Romaioi, or Christians of the Greek Church, and amongst whom would be found the chief supporters of an insurrection, are certainly of a mixed origin, sprung from Scythian colonists. Such arc the Albanians, the Maniotes, the Macedonian, Uulgarian, and Wallachian Greeks. And yet the whole nation, including, I presume, these Christians, has been laid down only at two millions and a half, of all ages and sexes, and consequently there is no part of Continental Greece to which a body of Turks might not be instantly brought, sufficient to quell any revolt: the Mahometans of Albania arc themselves equal to the task, and on a rising of the Giauours, the Infidels, would leave all private dissension, to accomplish such a work. The Greeks taken collectively, cannot, in fact, be so properly called an individual people, as a religious sect dissenting from the established church of the Ottoman Empire.

Click here to continue reading.

.png)